The Effect of Caffeine on a CDN’s image

We show that delivering an image from Washington D.C. to Austin, TX using Caffeine (1523.8 miles) is far faster than delivering an image from Dallas to Austin using HTTPS (195.1 miles) on a 3G connection. This experiment measures the use of Fastly and Caffeine together and separately while comparing against Akamai.

Key Conclusions

- On top of Fastly, Caffeine provides an additional 45% average improvement to customer traffic latency

- Caffeine and Fastly together unlock a combined 57% average improvement to customer traffic latency

- Fastly alone provides a 20% average improvement to customer traffic latency, whether or not Caffeine is used.

- These figures are for a residential WiFi connection. Caffeine unlocks additional performance on cellular networks.

- Caffeine significantly closes Fastly’s performance gap with Akamai on mobile

Experimental Design

Architecture

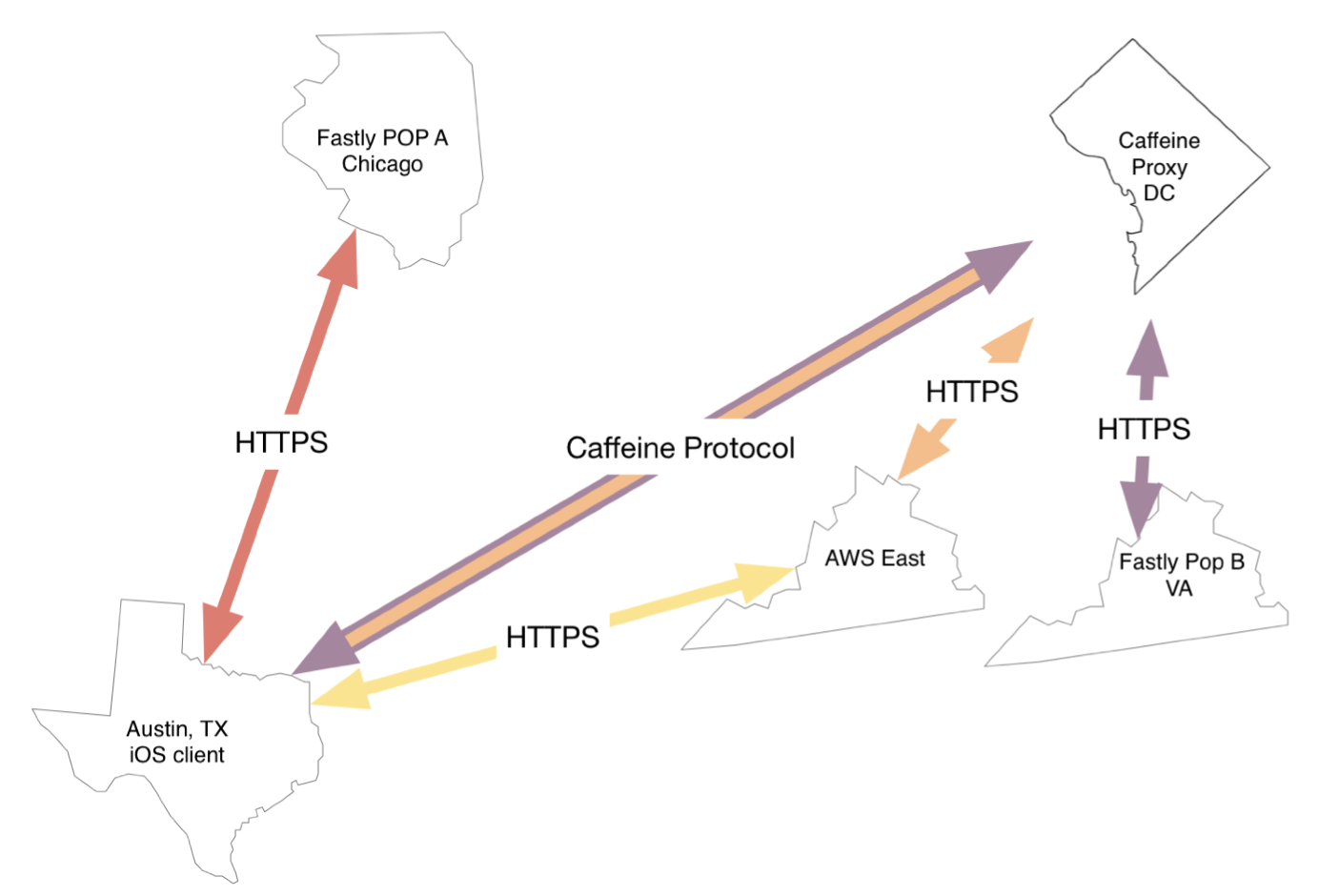

We set up the network architecture to perform our experiment.

| Node | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Client | Austin, TX | Central US location |

| Fastly POP A | Chicago, IL | Fastly-nominated POP from our client |

| Caffeine proxy server | Washington, DC | Existing production server for a customer deployment for AWS East |

| Fastly POP B | Ashburn, VA | Fastly-selected POP for our proxy server |

| S3-East POP | Ashburn, VA | S3 East location |

Client configuration

We placed a client on a residential WiFi connection in Austin, TX. Its characteristics were measured and results recorded to the following table:

| characteristic | value |

|---|---|

| download speed | 156mbit/s |

| upload speed | 20mbit/s |

| Fastly POP | 151.101.44.230 |

| avg. Fastly ping | 51ms |

| stdev Fastly ping | 14ms |

| S3-East POP | 54.231.32.99 |

| avg S3-East ping | 62ms |

| stdev S3-EAST ping | 11ms |

Proxy configuration

We measured our Caffeine proxy server and its characteristics are recorded in the following table:

| characteristic | value |

|---|---|

| download speed | 399mbit/s |

| upload speed | 781mbit/s |

| Fastly POP | 151.101.32.230 |

| avg. Fastly ping | 2.2ms |

| stdev Fastly ping | .068ms |

| S3-East POP | 54.231.98.144 |

| avg S3-East ping | 2.5ms |

| stdev S3-EAST ping | .065ms |

iOS application

We designed an iOS application to benchmark fetching a resource used by an actual Fastly customer. The resource was selected by examining a Fastly customer application to select a format (image) and size (62kb) to be fairly typical of mobile application traffic. The URL of the resource we chose was: https://secure.img1.wfrcdn.com/lf/205/hash/0/29643030/1/Top+Tools+for+Party-Starting+Treats.jpg. The domain in this URL is a Fastly customer’s alias for the Fastly CDN.

The following is standard benchmarking code for loading an image on iOS.

//avoid client-side caching

let config = NSURLSessionConfiguration.ephemeralSessionConfiguration()

config.addCaffeine()

let session = NSURLSession(configuration: config)

let request = NSMutableURLRequest(URL: NSURL(string: "https://secure.img1.wfrcdn.com/lf/205/hash/0/29643030/1/Top+Tools+for+Party-Starting+Treats.jpg")!)

//or use instead for S3 origin

//let request = NSMutableURLRequest(URL: NSURL(string: "https://proxeine.s3.amazonaws.com/Top%2BTools%2Bfor%2BParty-Starting%2BTreats.jpg")!)

request.HTTPMethod = "GET"

for _ in 0..<100 {

let stop = dispatch_semaphore_create(0)

let then = NSDate()

let _ = session.dataTaskWithRequest(request) { (data, res, err) in

print("\(NSDate().timeIntervalSinceDate(then))")

dispatch_semaphore_signal(stop)

}.resume()

dispatch_semaphore_wait(stop, DISPATCH_TIME_FOREVER)

sleep(3)

}

print("done")

Additionally, the following two lines of code enable Caffeine acceleration:

CaffeineHTTPProxy.start()

CaffeineHTTPProxy.allow("h*") //proxy all HTTP/HTTPS traffic

When enabled, Caffeine intercepts network traffic inside the iOS operating system and routes that traffic to a Caffeine server located in the Washington, DC area. Our server terminates the client connection and makes standard HTTP/HTTPS outbound requests to S3 and/or Fastly.

No caching is performed by any of our components (client or proxy server). All requests fly out to S3 or Fastly origins. We assume that Fastly caches customer data at its POP locations.

Results

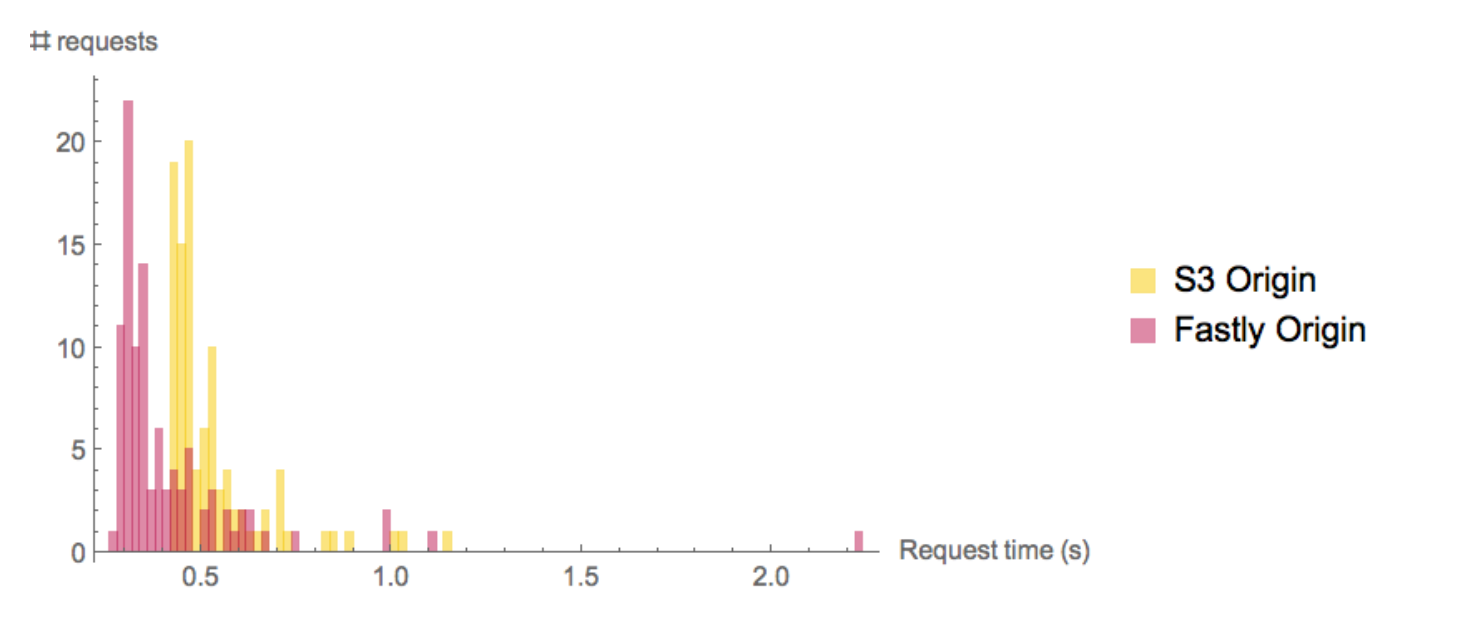

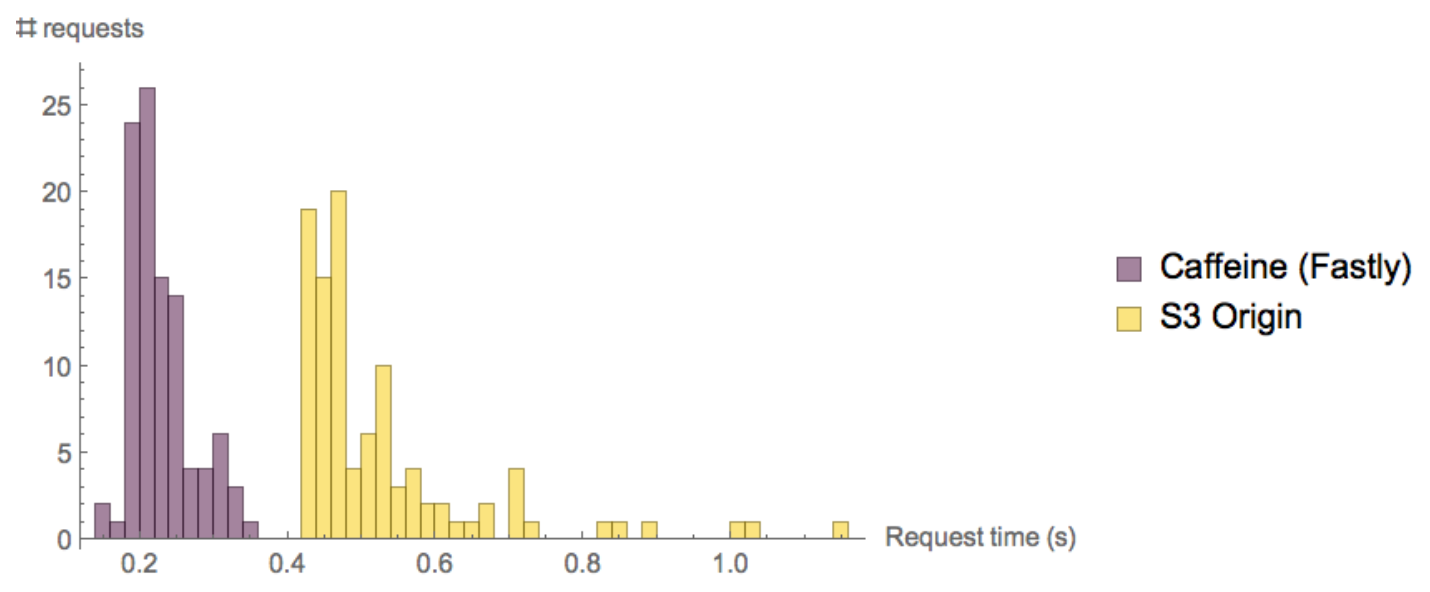

S3 Origin vs Fastly

We first compared the S3 Origin against Fastly, without using Caffeine technology. We expect Fastly to be faster than our S3 origin, and this result helps validate our experimental design.

We find that Fastly improves performance with statistical significance, p=1*10^-14. The improvement from Fastly is between 54ms and 162ms with 95% confidence.

Fastly reduces request times by an average of 108ms, an improvement of 20%.

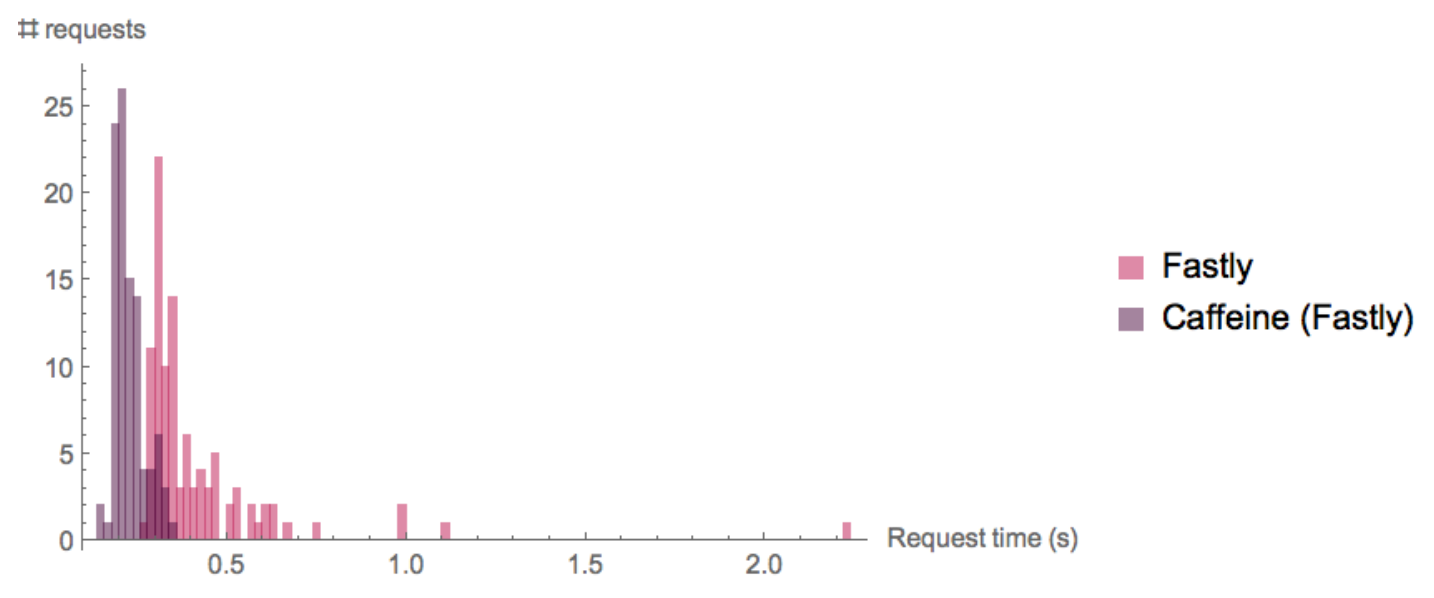

Fastly alone vs Fastly with Caffeine

We then added Caffeine technology to Fastly requests to measure any improvement.

We find that Caffeine improves Fastly performance with statistical significance, p=2*10^-30. The improvement from Caffeine is between 144ms and 240ms with 95% confidence.

Caffeine reduces Fastly request times by 193ms, an improvement of 45%.

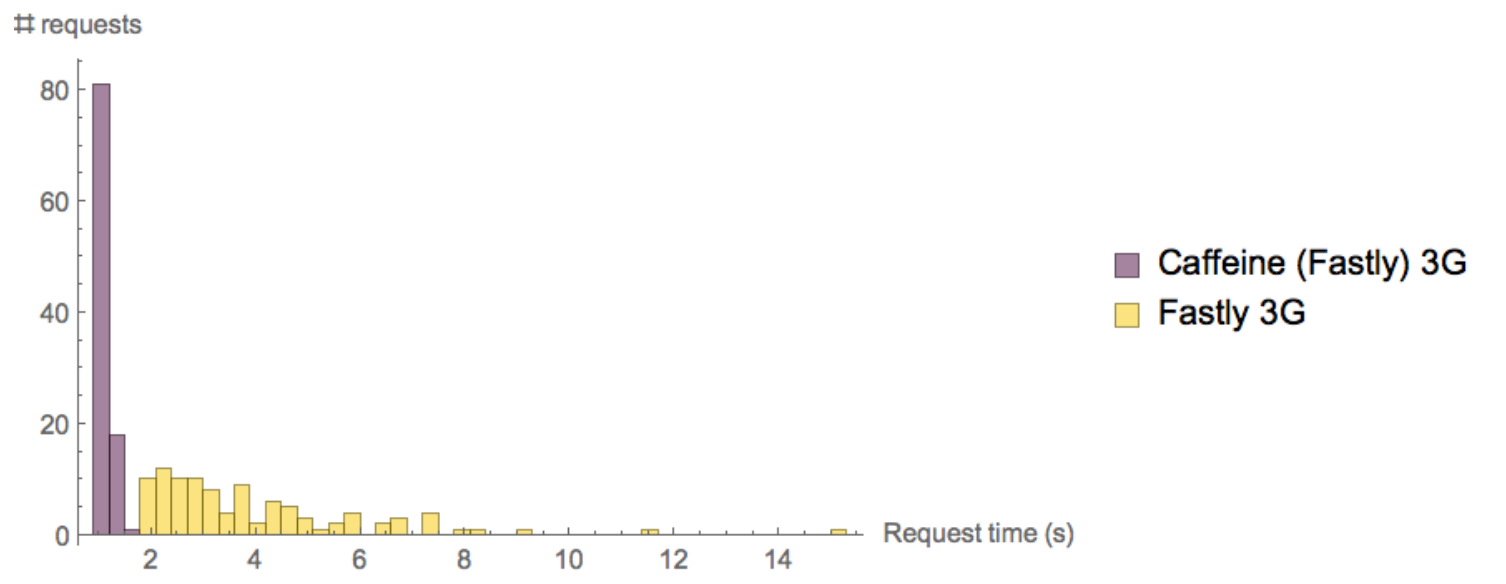

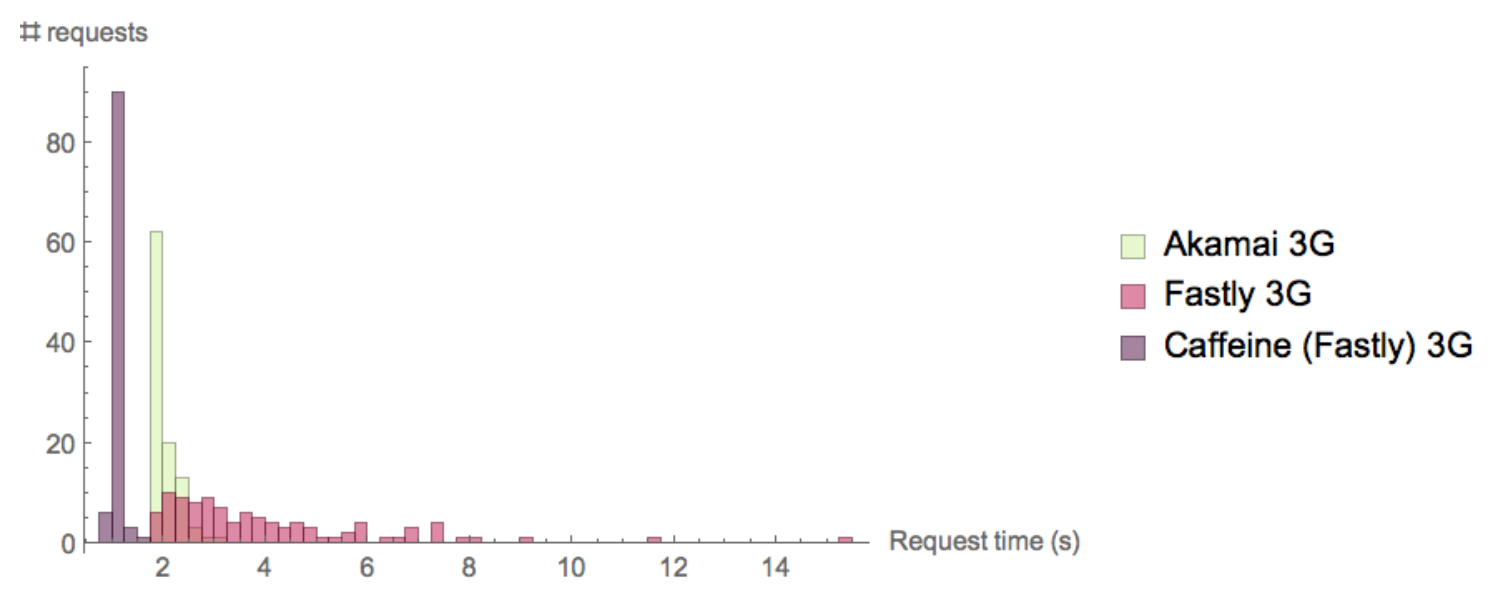

3G Performance

Mobile customers are often mobile. This places them on cellular networks that are crowded, have interference, and are otherwise much less well-behaved than residential WiFi or fiber-class networks. More and more internet users are mobile, with many of them in developing countries where networks behave more unpredictably. While bad networks always represent some performance degradation, Caffeine aggressively targets these cases and can often provide good user experiences in very bad environments.

We re-ran the above benchmark on a 3G network to see the effect in a poor customer environment.

Caffeine improved Fastly performance on this network with statistical significance, p=2*10^-34. The improvement from Caffeine is between 2.48s and 3.34s with 95% confidence.

Caffeine reduces Fastly request times on a 3G network by 2.91s, an improvement of 72%.

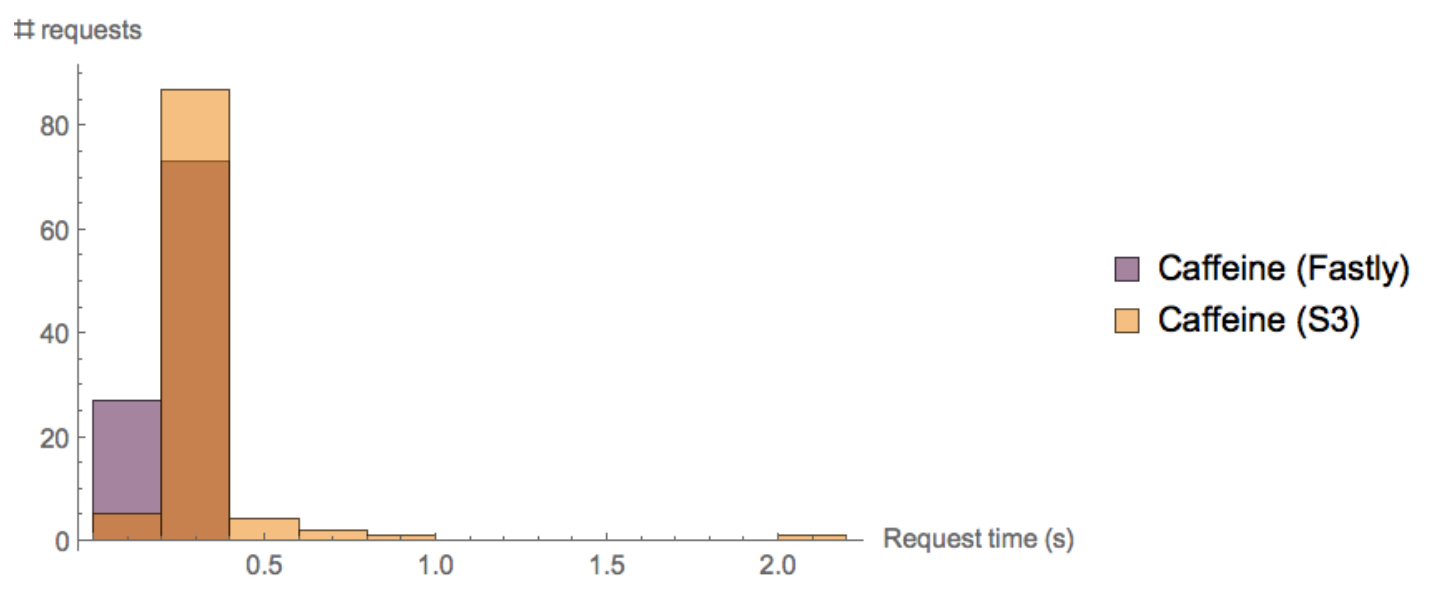

Better Together

We then compared Caffeine technology with an S3 origin against Caffeine technology with a Fastly origin. This quantifies the improvement Fastly contributes to a combined solution.

We find Fastly improves Caffeine performance with statistical significance, p=.0001. The improvement from Fastly is between 13ms and 98ms with 95% confidence.

Fastly reduces Caffeine request times by 55ms, an improvement of 20%. While this is in line with the 20% improvement from Fastly we measured earlier, we believe Fastly’s actual contribution to performance in this configuration is higher due to a limitation in our experimental design discussed below.

A prospective customer’s perspective

We studied a prospective customer evaluating both our offerings as a combined solution.

We find our combined technologies improve S3 performance with statistical significance, p=2*10^-34. The improvement from our combined technologies is between 273ms and 329ms with 95% confidence.

Our combined technologies improve request performance by 301ms, an improvement of 57%.

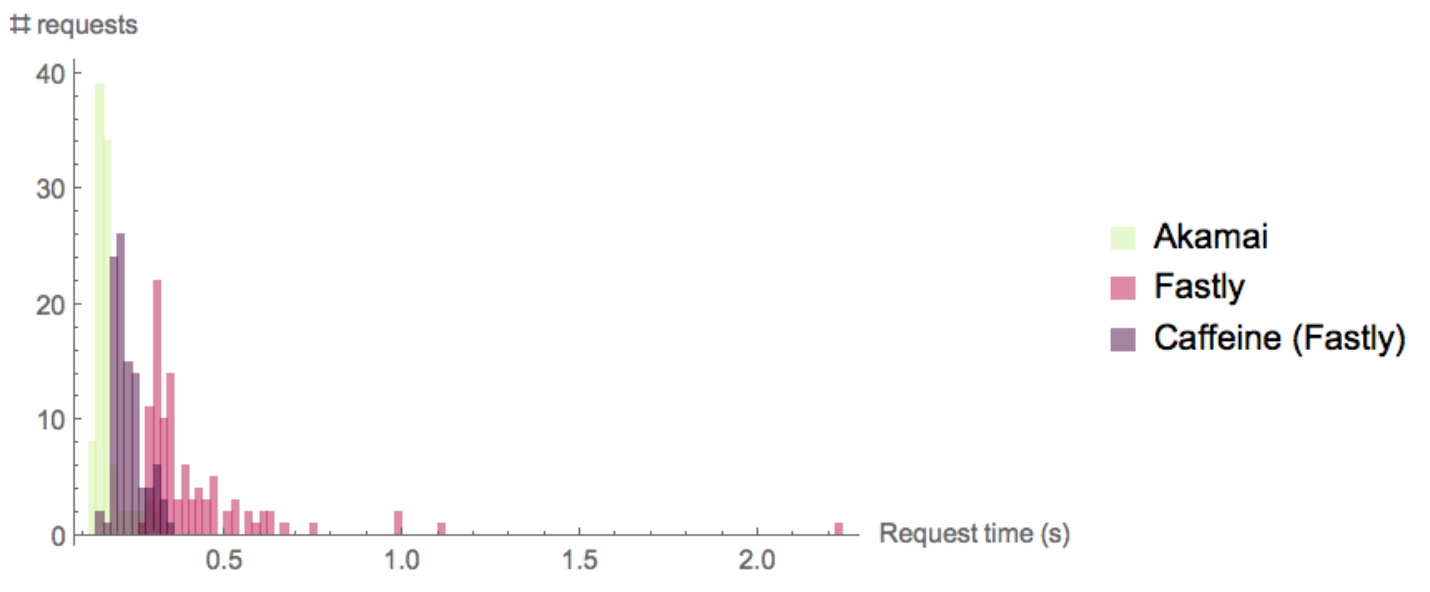

Comparison with Akamai

After seeing these initial results, we decided to extend our experiment to cross-compare our results with industry leader Akamai’s CDN platform. We reverse-engineered the NBC Sports iOS application, used (among other sporting events) to provide coverage for the 2014 and 2016 Olympics. We used a 62KB image served by Akamai to that application to collect the Akamai results for this test. URL: https://hdliveextra-a.akamaihd.net/HD/image_sports/mobile/QfcI2BDLZJpTx0razVw0Pv6YbidnUTYj_m60.jpg

Akamai has a node in Dallas, which provides a significant advantage to Akamai over the other scenarios in our test. It is much faster to reach Akamai’s Dallas node (32ms) from our client than either Fastly (51ms) or our Caffeine proxy server (61ms). Nonetheless, we find the results intriguing.

In this experiment, Akamai has a strong lead over Fastly, no doubt due to its closer point of presence. But interestingly, Caffeine technology substantially narrows the performance gap, even as it increases the total packet distance by nearly 8x. This suggests to us that Caffeine technology could help Fastly, or other CDNs, compete for mobile customers even without expanding their global footprints.

We re-ran this test in a 3G environment to see what effect, if any, our aggressive “bad network” protocol optimizations might have for mobile customers in crowded network environments. The result was stark:

In this environment, Akamai’s relatively consistent performance has a healthy lead over Fastly’s much more variable performance. But with the addition of Caffeine technology, the tables turn dramatically, placing Caffeine/Fastly performance in its own performance class. This is true even though Caffeine packets must travel nearly 3x the distance of the Akamai ones. These results are directly attributable to our mobile-focused protocol engineering, and demonstrate the power of a custom protocol approach.

Limitations

We recycled an existing production Caffeine proxy server for this experiment. While this helps more accurately determine performance under realistic workloads, it also increases distance (and decreases measured performance) for the Caffeine+Fastly configuration. Ideally, requests from Austin would reach a Caffeine proxy in Chicago and arrive at the “Fastly A POP” (see image from beginning). Unfortunately, we don’t currently have a server presence in Chicago, so these requests took a detour through DC, reducing the performance we measured in the Caffeine+Fastly configuration below the performance we would be able to see in a larger deployment.

Akamai’s Dallas location allows them a strong advantage over Fastly’s POP (Chicago) or our server (DC). Nonetheless, we find the Akamai comparison compelling and it suggests several interesting opportunities for future tests.

This experiment was performed at one client location and one proxy server location that were chosen arbitrarily from our existing deployments. We have not tested other client and server locations with Fastly and so results in other geographies may vary.

This experiment was performed with only 2 resources of 62kb size. We think these resources are pretty typical for iOS traffic, but requests of other sizes may cause performance to vary.

Due to a design detail of the Caffeine technology, the very first request made during an application session is slower than subsequent requests, by a factor of about 50%. Results reported here are for subsequent requests, which are by far the majority (>99.9%) of requests during an application session.

Learnings

In our experiments, the key contribution of Fastly, or CDNS at large, is moving the content close to the client in an edge blade architecture.

Caffeine accelerates both the upload and the download, which is certainly important to native mobile apps (they often have more uploads than they do downloads!). This feature was not discussed in this report, however, because there is no equivalent feature on CDNs.

The key contribution of Caffeine discussed in this write-up is improving the efficiency of the inevitable last-mile through aggressive protocol optimizations. Our results show we achieve large relative improvements over both enterprise-grade general-purpose HTTPS stacks (AWS) and highly performance-tuned stacks (Fastly, Akamai). This demonstrates that even the best HTTPS performance tuning cannot compete with very aggressive custom protocol design.

These improvements appear largely independent and therefore additive. Customers benefit best from using both technologies, not from using either one separately.

We believe that custom protocol engineering is an important tool in the overall performance portfolio, particularly for mobile customers, which are a large and growing segment. Our protocols work alongside and enhance traditional performance strategies, like POP deployments or TLS tuning to provide a combined customer solution. But they also provide new ways of thinking about performance that don’t have traditional drawbacks. Savvy partners should use an all-of-the-above performance strategy and lean on the strengths of each technology wherever those technologies work best to provide the best experience for their customers.

We think all of these results are quite encouraging, particularly given that our current technology is not well-optimized for the CDN case, and these results suggest to us that further improvement and optimization is possible.